I wrote this in the late 1990s as I was contemplating the coming Millennium and absorbed with Millennial Thinking and Optimism. I had not the slightest idea how things might unfold, with 9/11, the horrors of the Gulf War and its aftermath in the Middle East, our Environmental precipice, three very divergent Presidents, and the troubled, divided, and chaotic state of our country and our world today…

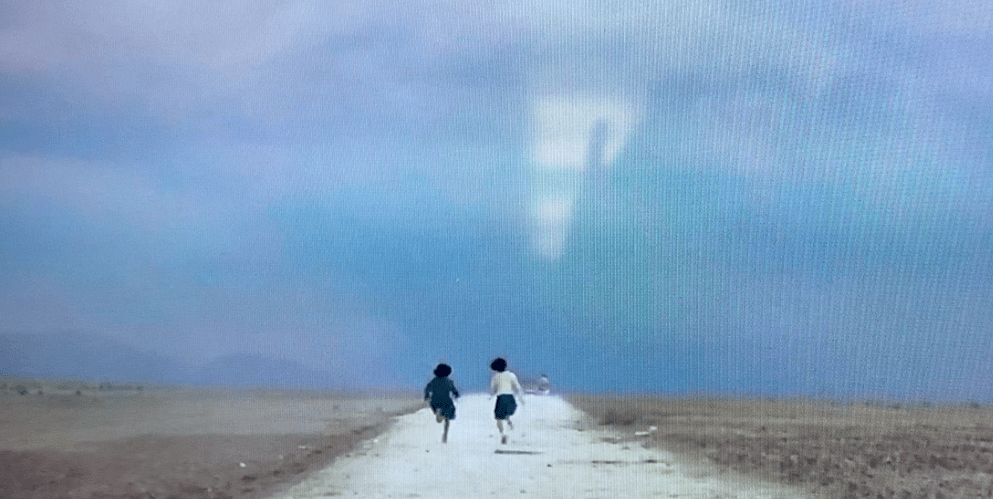

What does the future hold? What can we realistically do, now in the late 20th century, to insure a brighter future for ourselves and our children?

Current scenarios regarding the 21st century and what it will be like are fascinating and alluring, but at the same time frustrating and confusing. In listening to even the most informed and expert prognosticators, we are faced with two starkly opposite projections.

Therein lies our problem. On the one hand we are asked to imagine and anticipate a glittering, near utopian, Paradise in which most of the ills of the late 20th century will disappear forever. The dazzling array of scientific and technological advances, already dimly visible on the horizon, will bring astounding progress in every area of human civilization–communications, medicine, agriculture, manufacturing, space exploration–the list is endless. We will live in a tightly knit “global village” in which national and regional conflicts become increasingly a thing of the bygone and primitive past. Our highly integrated, multi-national economies will gradually eliminate the divisions between the First World, Third World, and Least Developed Countries. Democratic ways and advantages will inexorably spread to the most remote corners of the earth. Personal freedom, leisure, and creativity will be premium. We will even experience unexpected breakthroughs in understanding our origin and place in this marvelous and mysterious universe. Such discoveries will make our 19th and 20th century philosophical and theological perspectives appear strangely parochial and naive. Times might be tough getting where we are going, but we have the sense that our species, like an infant leaving the nursery, is going to come of age. We will put behind all the childish ways of our sad and tragic history and grow up into a new a promising future.

On the other hand, despite all hope and optimism, when one soberly and sanely “takes the pulse” of our current world, factoring in our all-too-human nature, quite the opposite picture can emerge. The staggering realities are familiar to us all, indeed, they compose our daily headlines: the irreversible pollution of air, land, and water; massive world debt; our crushing overpopulated cities with their seemingly unbreakable cycles of poverty, decay, crime, and drugs; our numerous moral, ethical, and social dilemmas; the constant outbreak of unsolvable regional disputes; and always, the ominous and absolutely stark possibility of a nuclear holocaust. Are we facing a slow but steady slide into some kind of an apocalyptic nightmare, despite all of our scientific and technological advances, and regardless of our best intentions?

What are we to make of these opposite visions of our future? Both are held by sincere, well informed, professional prognosticators. Both can be supported by an array of facts and hard evidence. Is this predictive enterprise wholly subjective, more reflective of individual psychological disposition than hard and fast “reality?”

Here we must resist two tendencies, common to most of us. First, we like to be optimistic; we prefer to believe the best. Imagine a President of the Earth giving his or her “State of the World Address” in the year 2020. Despite all problems and potential disasters we would want to hear a rousing speech that would rally us to our best collective efforts.

This is normal and natural. We want to believe that no matter what the challenge, somehow, we will muddle through it all. But the terrifying lessons of history tell us that things do not always “work out for the best” just because we wish it to be so. History offers us no guarantees; platitudes offer deceptive comfort. Second, we often have a tendency to be fatalistic. We sometimes feel, that given the incomparable nature of our problems, there is little we can do one way or the other. No matter what we think, or imagine, or do, things will tend to move along in patterned directions, largely beyond our control. Looking back at history, it is amazing how we easily assume that this or that event, good or bad, was almost “inevitable.”

I propose another course. I maintain that both of these disparate scenarios of the 21st century are “true.” We are speaking of the future, a future yet to be determined. Our best and most expert attempts to assess our situation, and look ahead, present us with the very ambiguity we find so confusing. Our problems are staggering, massive, and apocalyptic in their proportions. And at the same time, we stand on the threshold of the most incredible opportunities for that near-utopian world that humans have dreamed of for millennia. This complex and equivocal picture is essential for us. It is our reality. Perhaps it would help to go back to the turn of the last century. How did things look

in 1899, when the triumphs and the horrors of the 20th century were yet ahead? Frankly, such a look back makes looking forward a bit frightening. The 20th century opened with great optimism: science, technology, and the post-Enlightenment Weltanshauung combined to paint an extravagantly hopeful picture. It was almost wholly wrong. Can we expect to do any better?

I think we can. Our advantage is that we have lived through the ambiguities and horrors of the 20th century; yes–the good, the bad, and the ugly. We have seen it all, in combinations that have been unparalleled in world history: Apollo 11, Auschwitz, and Hiroshima–the towering symbols of our 20th century realities. We are not compelled to judge and guess about the future in the dim firelight of a forgotten or idealized past. We have no cause to naivelychant the praises of unbridled scientific advances or inevitable human progress. Therein lies our hope. So much that we face is new to our species. Our newly acquired, global “selfconsciousness” is our potential salvation. As individuals we remember, regret, plan, and dream. The 21st. century offers our species a collective opportunity, probably the first in human history, to do just that.