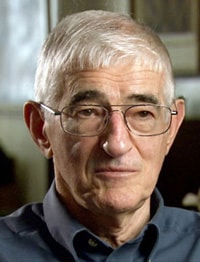

I have been thinking lately about the essential differences between Judaism and Christianity, or more properly, the kind of religion reflected in the Hebrew Bible and that of the Greek New Testament. In terms of definition and label I am neither a Jew nor a Christian — by that I mean the Mishnaic-Talmudic forms of the Classical Jewish faith that developed after Second Temple times, and the Orthodox Catholic versions of Christianity that developed in the West and East after Constantine. I am interested in religious and philosophical truth, but my training is that of an historian, so perhaps that is why I am drawn to the more ancient forms of these two faiths, i.e., the Hebrew faith as formulated by the Prophets and final redactors of the Hebrew Bible, and earliest Christianity as reflected in the New Testament. In considering these two “religions” or ways of thinking about God, the world and human purpose, I find that I am much more drawn to the former than the latter. Why is that so? What is it about the Hebrew Bible, even on a symbolic/mythological level, that seems to draw me so? Conversely, what is it about early Christianity, especially the systematic theologies of Paul or the Gospel of John, that puts me off so?

The Hebrew Bible’s Ambiguity

As for the Hebrew Bible, the whole notion of the One, true and living Creator, the God of Abraham is most appealing. Humans are seen as mortal, made of dust. Consequently, death and human history are taken very seriously. They are made in the image of God, capable of reason and free choice, of good as well as evil. God reveals Divine laws, the “Way” for humankind; a way that brings blessings not curses. The human race is seen starkly in its wayward and sinful condition, yet there are those who love and follow this true God in the midst of it all. Their mission is to be a witness to the “nations” (non-believers) and to bring about the establishment of righteousness, justice, and peace on the earth. On an individual level, as in Psalms or Job, there is a lot of questioning after God. The ways of God are far from clear. There is certainly expectation of intervention, a longing for God’s help and care, but simplistic view of things is rejected.The Hebrew canon (with the exception of Daniel) essentially closes with this kind of ambiguity.

Humans are to seek God, to live the ways of God on the earth, but much is left open, whether individual ideas of immortality or broader schemes of historical plans and purposes. The essential idea of the Shema is the heart of it all: God’s people are to acknowledge God’s nature, to love God, and to follow the ways of God revealed in the Torah and Prophets. Ecclesiastes shows clearly how many questions are simply left unanswered. True, the Prophets do offer many predictions of a restoration of Israel and even a transformed age to come. However, the texts themselves express lament-full doubts about when, and even whether, this will ever come (e.g., Psalm 89; Habakkuk). The Hebrew canon closes with II Chronicles 36:23 — “Let him go up” — which could bear some symbolic meaning beyond the proclamation by Cyrus of the end of the Persian exile of the Jews. It comes at the very beginning of the Second Temple period, as if to say: all if open, Israel’s future is still unwritten, and individuals are called to respond.

The New Testament’s Answers

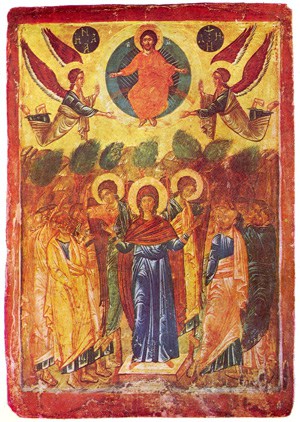

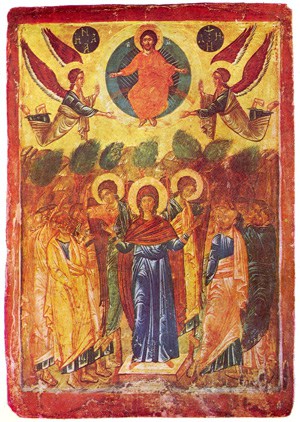

The New Testament comes out of a wholly different milieu. First, it is part and parcel of the broad changes in religious thought that we know as “Hellenization.” It is characterized by a vast and expanded dualistic cosmos, an emphasis on immortality and personal salvation, i.e., on escaping this world for a better heavenly life. At the same time, and to be more specific, it is absolutely and completely dominated by an apocalyptic world view of things, whereby all will be soon resolved by the decisive intervention of God, the End of the Age, the last great Judgment, and the eternal Kingdom of God. In addition, the Christology that develops, even in the first century, is thoroughly “Hellenistic,” with Jesus the human transformed into the pre- existent, divine, Son of God, who sits at the right hand of God and is the Lord of the cosmos. The whole complex of ideas about multiple levels of heaven, fate, angels, demons, miracles and magic abound. It is as if all the questions that the Hebrew Bible only begins to explore — questions about theodicy, justice, human purpose, history, death, sin — are all suddenly answered with a loud and resounding “Yes!” There is little, if any, struggle left. There are few haunting questions, and no genuine tragedy or meaningless suffering. All is guaranteed; all will shortly be worked out.

Of course, various attempts are made to reinterpret this early Christianity for our time, usually in terms of ethics or some existential core of truth, but early Christianity rests on two essential points, both of which resist easy demythologization: it is a religious movement built upon an apocalyptic view of history; and an evaluation of Jesus as a Hellenistic deity, i.e., a pre-existent divine Savior God in whom all ultimate meaning rests. If these are unacceptable in the modern world, or incompatible with the fundamental Hebrew view of things, then the whole system become difficult, it not superfluous.This is not to say that there are no similar problems with the Hebrew Bible, but fundamentally things are different. Even Daniel, that begins down the path of fantastic apocalyptic answers to hard human questions about the meaning of history, is somewhat vague about it all. That is one good reason Daniel was never included among the Prophets in the Jewish canon. Of course, the Hebrew Bible, like the New Testament, is framed around God’s intervention in human history: God calls Abraham, delivers Israel to Egypt, reveals the Torah at Sinai, gives the Land to the Israelites, expels them, promises to bring them back, etc. It is an interventionist story. And yet, in contrast to the New Testament, God is often silent, there are many dark areas, many unanswered queries, and much doubt and debate expressed about it all, even within the texts themselves. But more important, the two of the major problems for the later Hellenistic age–human mortality and theodicy, are left largely unaddressed.

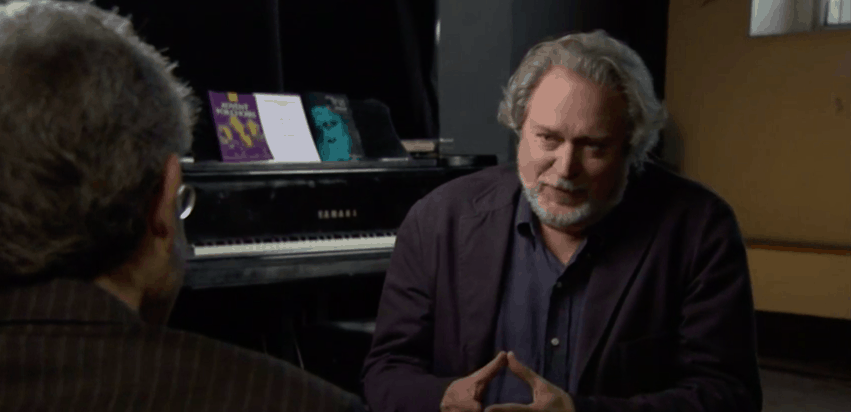

Some years ago I read a fascinating interview in Biblical Archaeology Reviewby editor Hershel Shanks with Jewish thinker and Holocaust surviver Elie Wiesel and renowned Harvard Biblical scholar Frank Moore Cross (July/August, 2004). In one short but significant section Professor Cross comments on how being a Christian affects his relationship to the Hebrew Bible, which is his field of concentration. I find his comments enlightening, and though here he only focuses on one issue, that of the magical/demonic world of late antiquity, the implications of what he states appear to parallel my thoughts here:

Shanks: How does being a Christian affect your relationship to the Hebrew Bible?

Cross: Happily, I come out of a Calvinist tradition in which the Hebrew Bible carries as much authority as the New Testament. No different weight is given to one or the other. The Bible is one, Old and New, in my particular tradition. My own interest is far more in the Hebrew Bible. My religion is more personally related to the Hebrew Bible than the New Testament.

Shanks: What does that mean?

Cross: I find myself a little uncomfortable in the New Testament environment. And this is also true of what I would call late Judaism, the Judaism of the Second Temple and later. With the Hebrew Bible, you’re living in an austere world. When you come to the New Testament you can’t even swing a cat without hitting three demons and two spirits. And magic becomes something that is everywhere. In the Hebrew Bible this sort of thing doesn’t go on.

Shanks: You have miracles, yes, but they’re not the work, normally, of demons.

Cross goes on to explain his approach to the Hebrew Bible as one that takes a critical view of its stories and narratives, with lots of question marks regarding “historicity,” while appreciating the power and meaning of its epics, myths, and symbols.

My Attachment to Both Canons

Began my career as a “Bible scholar” and my college majors were Greek and Bible, so I still, broadly, consider myself a student of the Bible–that includes Hebrew Bible as well as New Testament, and of course my specialty is Christian Origins. I find myself drawn to these biblical texts, these ideas and images, tempered through the sifting and sorting out that comes through historical criticism in an effort to separate myth and history. I want to neither devaluing the former nor ignore the latter. The opening chapters of Genesis powerfully expresses any number of fundamental perceptions around which my own approach to human life is shaped. God as the “Power of all powers” (Elohim) orders the chaotic planet earth with humans, created from the, “dust of the earth,” but reflecting the image of the Elohim. Humans and beasts are given only “green herbs” to eat. It is only after the Flood that meat is allowed, when sin and violence had filled the earth. Are we to re-present to the world in this small way, this way of peace from which we have fallen? It is a powerful idea, as Isaiah himself knew when he spoke of the child’s leading the lion, the infant’s playing at the nest of the scorpion–“They will not hurt nor destroy on all My holy mountain, says the LORD” (Isa. 11:9). Human are to “dress and keep” the garden and have both the power and responsibility to exercise custody over the good earth, even in the world of “thorns and thistles” outside the gates of Eden. When it comes to the New Testament the cosmically triumphant theologies of Paul and John are dominant, but running through the Gospel materials are layers in which one finds a Jesus wedded to the ethics and perspectives of the Hebrew Prophets, not a deity but one who is vulnerable, a “human all-to-human,” one who, as Schweitzer puts it, throws himself onto the wheel of history in an effort to move things forward but is tragically crushed. Those contingent, conditional, and open-ended aspects of the Jesus story I find most compelling, and most in keeping with the Hebrew view of history and human possibilities.

A version of these thoughts was published in the Journal of Reform Judaism (Summer, 1990): 35-38.