You can also listen to an extended interview I did this week on this translation and what makes it different, just posted on my Youtube Channel here.

What is the best-known verse in the Bible—one that millions could quote immediately by heart? Christians might say John 3:16—after all, one even sees placards and signs reading “John 3:16” at sporting stadiums! But I think the very first verse of the Bible—Genesis 1:1—most likely would win the universal familiarity content:

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.

I have a replica of the Geneva Bible, published in 1560, that was the standard up through the 17th century—even over the King James for a time. It has a very similar translation:

In the beginning God created heaven and the earth.

What few realize is that most scholars now consider this translation not only faulty but seriously misleading. The problem is that these older translations, now so enshrined in our memories, have ignored an important element of grammar—namely that the first word, בראשית/bereshit—is in the construct state, making it a temporal participle, connected to what follows. A good parallel is Jeremiah 26:1, which clearly means, “At the beginning of the reign of Jehoiakim . . .,” or “When Jehoiakim began to reign . . .” with what follows describing the state of things at such a beginning. The opening verses of Genesis clearly reflect the same grammatical construction.

In other words, it is not a simple declarative sentence about the creation of everything by God from nothing. It is rather a description of the state of the “skies and the land” when God began to create things—bringing order out of the water covered earth that was without form and empty.

I well remember when the New English Bible was published in the 1960s when I was in college that its translation of this single verse cause great consternation on the part of traditional Bible readers. The “liberal scholars” were trying to water down the Creation Story, we were told. Everyone knew Genesis 1:1 was about the “origin of the universe,” to put it in modern terms.

Gradually other modern translations followed suit, including the Jewish Publication Society’s Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures (1985), and of course Fox, Alter, and others. Even the New Revised Standard Version, and its predecessor, the Revised Standard Version, included a variant note: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth…” The notes of the New English Translation (NET) Bible, hedge a bit, taking that first word as in the absolute state—but then in a note explaining that the construct state is nothing to get worried about—as if they prefer it but can’t bring themselves to put it in the text.

Translations must sell, no matter how accurate they claim to be, and changing the first verse of the Bible is not a good marketing strategy—to say the least!

For more on this see my blog post: “Is the Best Known Verse in the Bible Mistranslated?”

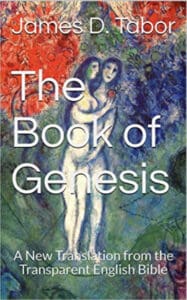

I recently published a new English translation of the Book of Genesis with notes—the first volume of the Transparent English Bible (TEB). It is available on Amazon in all formats, and you can look inside and browse to get an idea of my approach. Prices on all are significantly reduced for this Summer Sale.

There is an ancient Jewish adage regarding translating the Scriptures, “One who translates a verse literally is misrepresenting the text, but one who adds anything of his own is a blasphemer.” Modern translators of the Bible continue to echo, in more sophisticated debate, the dilemma of this ancient bit of wisdom. The literal method of translation seeks to convey an exact sense of the words and the structure of the original language, while the paraphrase, or “dynamic equivalent” method, purposely recasts the essential “thought” of the original into the natural idiom and flow of the second language. The problem is that an overly naïve literalism easily becomes nonsense, while “recasting thought” can end up obscuring or even altering the richness of the original text. The TEB is decidedly on the “literal” side of this spectrum, although the concept of transparency better conveys its theory and method.

The following examples—some of my favorites, taken directly from the TEB translation of Genesis, allow one to see the many important ways this new translation differs from the New International Version and the New Revised Standard Version, the two best-selling modern English translations.

NIV: “Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the expanse of the sky.”

NRSV: “Let the waters bring forth swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the dome of the sky.”

- TEB: “Let the waters swarm a swarm of living life-breathers and let the flyer fly upon the land, upon the face of the expanse of the skies.” (1:20)

Here are three examples of poetic consonance in one sentence: with Hebrew nouns and verbs echoing one another: “swarm a swarm” “living life-breathers” and “let the flyer fly.” Comparing translations, the TEB is not only transparently beautiful but it is more literal in reflecting an accurate approximation of the original Hebrew terms. These “life-breathers” are creatures, no doubt, but their distinguishing characteristic is possession of the “living life-breath.” It is this factor that then binds the birds, land animals, and human beings together, as explicitly stated in v. 30. Also, although “birds” is likely intended by the Hebrew word “flyer,” the word itself has a more generic meaning that the TEB retains.

Throughout the TEB one constantly encounters refreshing and fascinating idioms that are found in the original Hebrew. For example in Genesis 29:1 we read: “And Jacob lifted his two feet, and walked toward the land of the sons of the east “ The NRSV has: “Then Jacob went on his journey, and came to the land of the people of the east,” while the NIV has: “Then Jacob continued on his journey and came to the land of the eastern peoples.” In Genesis 12:9 the TEB reads: “And Abraham pulled up stakes, walking, and pulling up stakes toward the Negev,” The NRSV simply has: “And Abram journeyed on by stages toward the Negev,” while the NIV has “Then Abram set out and continued towards the Negev.” When you get up early in Hebrew you “cause to shoulder up” (see Gen 22:3), a reference to packing up and loading the animals for a journey. All three versions are understandable in terms of the basic meaning, but the TEB offers the English reader a glimpse into the colorful way that Hebrew actually expresses such common ideas.

The Biblical texts at times can be extremely repetitious, both in narrative style and vocabulary. Often translators are tempted to “smooth things out” a bit, forcing the original languages to conform more closely to modern English usage. Genesis 2:23 reads: (TEB) “This one, this time—bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh! This one will be called woman, because from a man this one was taken.” In Hebrew the feminine demonstrative pronoun (“this one”) is repeated three times in a single sentence. Genesis 11:6 (TEB) says: “This they begin to do, and now nothing is restrained from them of all that they have planned to do.” Both the NIV and the NRSV put “nothing will be impossible for them,” which is surely the meaning, and even much conventional English, but it removes the “flavor and flow” of the Hebrew text.

Professor Arthur Droge, who has produced what I consider to be the best translation of the Quran in English—also with notes, offers this evaluation of this new translation:

“Finally, a truly transparent translation! I have taught biblical texts for almost 25 years and have longed for a translation that didn’t pull any punches when it came to the difficult passages, or that didn’t try to “spin” the meaning of the text in the interests of later theology and doctrine (whether Jewish or Christian). Tabor’s translation of Genesis renders the Hebrew not just with unparalleled accuracy and fidelity to the text, it also offers readers a sense of the unfamiliar elegance and strange power of the original. Beautifully conceived and executed, Tabor’s translation is the result of a lifetime of critical learning and scholarly acumen. It is also a courageous undertaking. I have no doubt that it will quickly become the standard.”